It’s A Wonderful Life—But a Terrible Business Model

George Bailey wasn’t running a building and loan — he was running a Masterclass in what not to do in business

Reading Time: 10 minutes

Every holiday season, we revisit It’s a Wonderful Life — the Jimmy Stewart classic that functions less as entertainment than as an annual recalibration for adults measuring the distance between ambition and outcome. For the past three years, I've been writing an essay on the film after watching it on television. That's the gift films — especially great ones give us — each time you see it you can find something new. This year beneath the tinsel and the warm fuzzies lies something darker — and, yes, shockingly instructive for event planners, executives, and anyone who’s ever run a P&L.

Most people watch the movie and see redemption. What savvy strategists should see are management missteps, leadership blind spots, and a character study in why good intentions don’t make good results.

If You Hate Your Job, You Cannot Lead

George Bailey doesn’t quietly dislike his job. He resentfully detests it. From the moment the film opens, his longing for adventure and disdain for the family business permeate every decision he makes. Negativity becomes his default lens — not just on work, but on relationships, risk and even opportunity.

This isn’t cinematic angst — it’s a business warning. When leaders carry resentment into the boardroom, every challenge looks like a burden, every decision feels like a compromise of the soul and every trajectory becomes reactive instead of proactive. Bailey’s internal resistance infects his team, his network and ultimately his ability to grow his enterprise.

Key takeaway: Passion isn’t optional in leadership — it’s a strategic asset. Leaders without passion burn out the organizations they seek to sustain.

Collaboration Is Not Optional — It’s a Competitive Advantage

Remember Sam Wainwright? He’s the flashy, wealthy counterpart to George — the guy with ambition, a rolodex and an obnoxious streak a mile wide. George doesn’t want any of that world, and so he pushes Sam away, confusing simplicity with virtue.

But from a business lens, this is a classic strategic blind spot. Sam isn’t a threat — he’s a potential ally. When you recoil from collaboration because it triggers envy, insecurity, or you just plain don't like someone, you shrink your opportunity set. You focus only on your story while ignoring the stories others could help you write more successfully.

Key takeaway: In modern organizations, network effects and partnership leverage are as important as balance sheet strength.

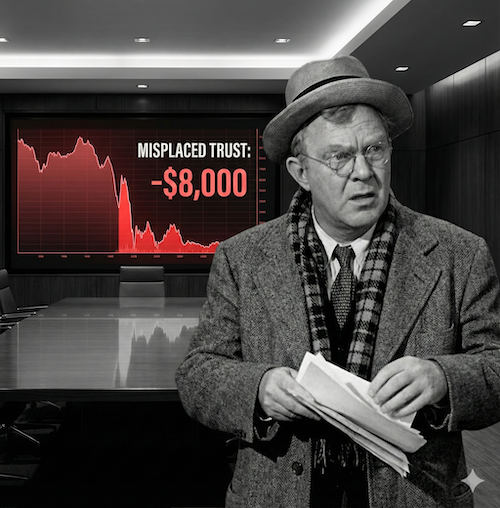

Misreading Talent Is a Risk Few Leaders Can Afford

One of the movie’s pivotal plot points — Uncle Billy misplacing $8,000 — isn’t just a dramatic turn. It’s a metaphor for the consequences of misplaced trust and poor talent assessment. George assigns critical responsibility to a character who is neither trained nor temperamentally suited for it.

This isn’t just a narrative device — it’s a leadership flaw. Modern executives know that talent optimization isn’t soft talk. It’s a strategic discipline. Putting people in roles that match their capabilities — not their familiarity — differentiates resilient organizations from fragile ones.

Key takeaway: Emotional loyalty doesn’t equal operational competence. Leaders who confuse the two pay for it with performance.

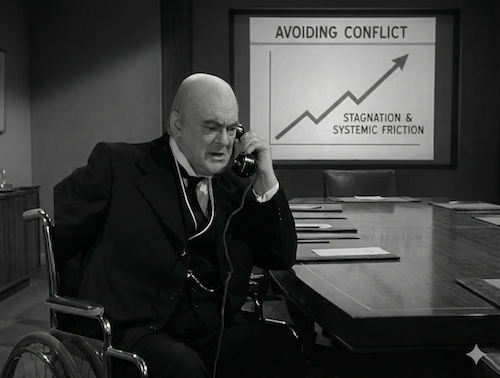

Avoiding Conflict Doesn’t Build Peace — It Builds Resentment

George’s handling of Mr. Potter is framed as a cautionary tale about polarization in leadership. Instead of approaching conflict with strategy, curiosity, or negotiation, George retreats into suspicion and resentment.

In today’s hyper-polarized business environment, leaders who avoid the hard conversations — who refuse to bridge ideological or operational divides — end up with silos, systemic friction, and stagnation. George’s approach amplifies the problem because it’s rooted in emotion rather than strategy.

Key takeaway: Conflict isn’t inherently destructive — mismanaged conflict is.

Nostalgia Doesn’t Translate to Strategy

Here’s the twist that most interpretations of the film unintentionally point toward: The story as most people tell it is about community and heart. What the real story should be about is strategic misalignment and the disconnect between intention and performance.

George Bailey is beloved because he sacrifices himself for others — but that sacrifice is also his downfall as a leader. He never optimizes for success; he optimizes for martyrdom. In a business context, that’s not nobility — it’s inefficiency. That’s the part of the story we often skip over, but it matters — especially when we’re trying to build organizations that survive, grow, and thrive.

Key takeaway: Emotion fuels culture. Strategy drives results. The two are not interchangeable.

The Real Hero of It's a Wonderful Life Is Mary

The ending of the film is a case study in invisible leadership. By the time George Bailey runs through Bedford Falls shouting “Merry Christmas!” the movie has already told us something essential — and deeply uncomfortable about leadership.

George doesn’t save himself.

Mary does.

The famous final scene where the neighbors pour into the Bailey living room, cash in hand, to rescue George from ruin is often framed as proof that kindness compounds. But that reading misses the deeper truth hiding in plain sight. Community doesn’t rally around values. It rallies around relationships. And Mary, in tandem with George, has been building those relationships all along.

Quietly. Strategically. Relentlessly.

Key takeaway: Mary was running the network while George was running away from it.

Two Redemptions, Two Revelations

George Bailey is redeemed not because his business is saved, but because his perspective is finally corrected. The angel Clarence doesn’t show him a better balance sheet; he shows him a truer ledger — one that measures worth in lives altered, not ambitions postponed. George learns, late but not too late, that significance isn’t always loud or self-authored. Sometimes it’s cumulative. Sometimes it’s invisible. And sometimes it only reveals itself when the alternative is absolute absence.

Mary Bailey mobilizes community and in doing so, experiences her own quiet awakening. What begins as crisis response becomes self-recognition. In rallying Bedford Falls, Mary realizes she is not merely a steward of George’s dream, but a force in her own right: a builder of trust, a curator of relationships, a leader whose influence has been accruing interest for years. The moment the room fills is also the moment that the scope of Mary's power — not borrowed, not secondary, but intrinsic — is revealed.

Key takeaway: Together, their arcs offer the film’s most modern insight: redemption isn’t always about being saved. Sometimes it’s about finally seeing your life, your work and your ability to shape outcomes as they truly are.

The Ending Isn’t a Miracle — It’s a Liquidity Event

The popular reading of the ending is theological: angels, grace, redemption. But strip away the carols and what you’re left with is a remarkably modern business lesson.

Mary doesn’t create goodwill in the final scene. She liquidates it.

Every dollar tossed onto the table represents a relationship previously earned. Every neighbor who shows up does so not because George is “good,” but because Mary made them feel seen, valued, and connected — long before anyone knew there would be a crisis.

George was the brand.

Mary was the platform.

All these years later this scene still makes modern viewers uncomfortable. There’s a reason Mary’s role often gets minimized in retrospectives. Her leadership style doesn’t conform to the mythology we prefer.

She isn’t charismatic.

She isn’t visionary.

She doesn’t dominate rooms.

She builds social capital — a form of currency many organizations still undervalue because it doesn’t show up neatly on balance sheets.

This is the invisible labor of power and stakeholder management at its finest.

Key takeaway: When the market turns volatile, it's the existing platform that holds things together — but only if you know how to use it. Mary understands something George never quite does: systems don’t save people — networks do.

Business Ethics, Bedford Falls Edition: Mr. Potter and the $8,000 That Tells Us Everything

If George Bailey represents the emotional extremes of leadership, Mr. Potter represents its ethical vacuum.

Potter’s quiet theft of the missing $8,000 — pocketed with a flick of the wrist and never acknowledged again — is one of the most chilling moments in It's a Wonderful Life. Not because it’s dramatic, but because it’s banal. There’s no villain monologue. No moral reckoning. Just entitlement, silence, and structural power doing what it does best. This isn’t a crime of desperation. It’s a crime of impunity. Potter doesn’t break the rules — he operates above them.

He controls the capital.

He controls the leverage.

He controls the narrative.

What makes Potter fascinating — and deeply modern — is that he doesn’t see himself as unethical. He sees himself as inevitable. This is a portrait of old money behavior: arrogant, unchallenged, and convinced of its own righteousness. The $8,000 isn’t stolen in a back alley. It’s absorbed into a system designed to protect those at the top from consequence. Potter understands something many contemporary executives understand all too well: ethics are often enforced downward, not upward.

Key takeaway: This is a textbook example of moral hazard — when power shields decision-makers from the risks of their own misconduct.

The Most Damaging Ethical Failure Is the One No One Confronts

Here’s the part that still stings: Potter is never held accountable.

Not legally.

Not socially.

Not reputationally.

George nearly dies under the weight of a mistake he didn’t commit, while Potter faces no scrutiny for a theft that could have destroyed a community institution. The message is subtle but devastating: systems built without ethical guardrails don’t just fail — they choose who gets sacrificed when they do.

Potter isn’t dangerous because he’s greedy. He’s dangerous because he’s normalized. His actions expose the difference between legal behavior and ethical behavior — a gap many organizations still struggle to close. He follows the letter of power while violating the spirit of responsibility. And because no one challenges him, the system quietly validates his worldview.

Key takeaway: This is the ethical trap leaders fall into when governance is weak and culture is deferential: wrongdoing becomes invisible, not because it’s rare, but because it’s expected.

The Uncomfortable Truth the Film Leaves Us With

The community saves George. No one saves the system.

Potter remains untouched, which may be the film’s most honest ending of all. Because real ethical reform rarely comes from goodwill alone — it requires oversight, accountability and the courage to confront power directly.

It’s a Wonderful Life is remembered as a story about kindness. But tucked inside is a sharper warning:

A business can survive bad luck.

It can even survive bad leadership.

But it cannot survive unchecked power dressed up as respectability.

In the end, It’s a Wonderful Life offers not one redemption, but two revelations. George Bailey is saved by a recalibration of value—he finally understands that a life doesn’t need grand ambition to be consequential, only sustained impact.

Meanwhile, Mary Bailey discovers something just as profound: that the quiet work of connection is, in fact, power. By mobilizing Bedford Falls, she recognizes her own ability to move people, activate trust and shape outcomes — not as an extension of George, but as a leader in her own right.

Mr. Potter? He walks away richer — his power preserved, his behavior normalized and the system that enabled both unbroken.

And that, more than angels or bells, is an ethical lesson that still resonates today.

Any thoughts, opinions, or news? Please share them with me at vince@meetingsevents.com.

Photos by Gemini